Need2Know - Substance Use and Primary Care

Substance use refers to the harmful use of psychoactive substances, including alcohol and illicit drugs, despite harmful consequences to users and others. Not all substance abuse ends in substance use disorder. Substance use disorder (SUD) is the clinical terminology for addiction. Compulsive and persistent behaviours often characterise addiction, as does tolerance (engaging in the behaviour or taking the substance) and withdrawal symptoms (negative physical and psychological experiences triggered by abstinence from the behaviour or substance of choice).

Over the years, the classification of what constitutes addiction has gone beyond alcohol and illicit drugs to include behavioural addiction (such as gambling), while others like internet gaming, sex, shopping and exercise have not been established as a diagnostic term yet. The impact of substance abuse is far-reaching, including negative health consequences, heavy financial burdens, and reduced healthy years. It is noted that for every person living with dependence, many more are at varying risk levels. And yet, often many of us lack an understanding of these connections or scientific evidence behind them, especially when it comes to what works best in preventing and addressing substance use in an integrated way.

Here is what you “need to know” from the evidence base.

This brief has been authored by Chinyere Nduu Okoro, Addiction Clinician (Nigeria)

Possibilities, Challenges and Recommendations

1. Substance use disorders occur on a spectrum

Over 400 million people (that is about 7% of the global population) aged 15 and older live with alcohol use disorders. Additionally, in 2021, 39.5 million lived with drug use disorders while at least 3 million deaths occur yearly due to alcohol and drug use disorders. Yet, it is established that addiction occurs on a spectrum.

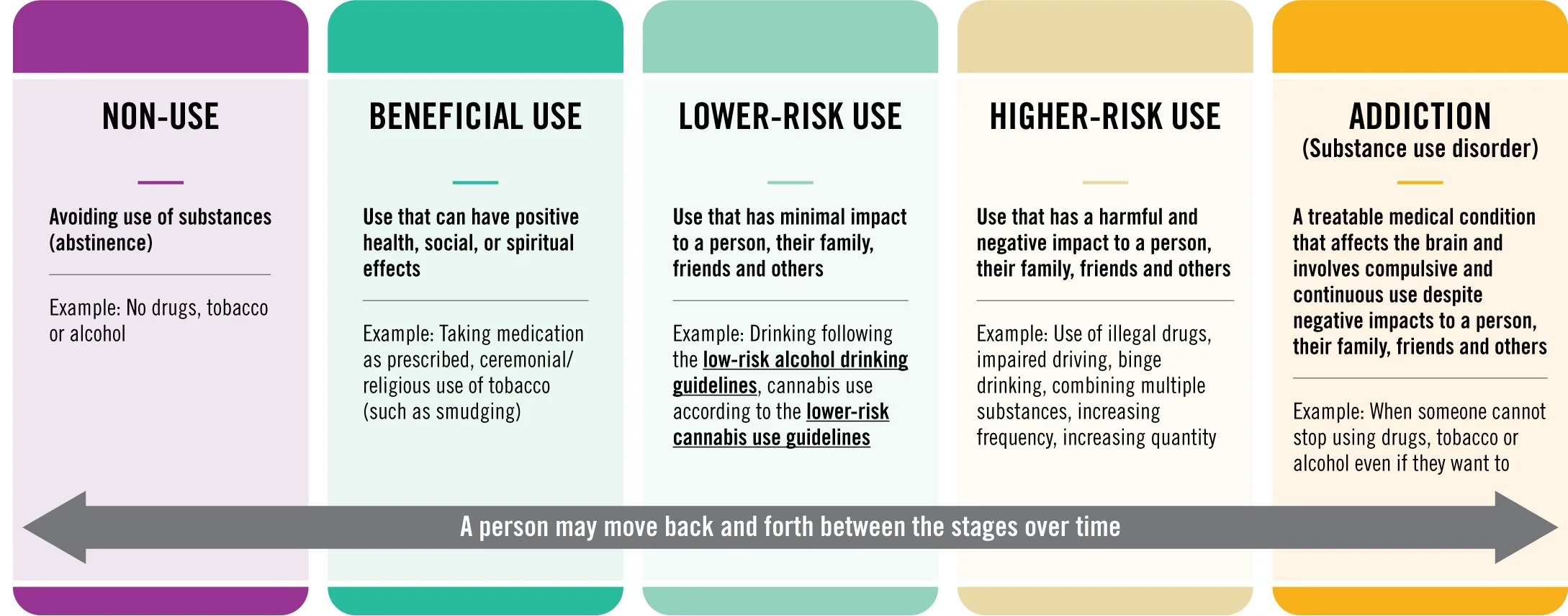

Figure: Substance Use Spectrum

This spectrum indicates that numerous people’s use of alcohol, psychoactive substances, or even addictive behaviours, like gambling, engage in a level that puts them at risk even if they have not developed dependence. No one is immune to dependence or addiction. As such, many of us likely fall somewhere along this spectrum, making us vulnerable to developing an addiction. The impact of substance use on health and development is recognized in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, through Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) health target 3.5, which calls for the strengthened prevention of substance use. The essence of this is to reduce the health and socioeconomic burdens of substance abuse and implement interventions at varying systemic levels to prevent and treat SUDs.

Achieving this requires prevention and care across the entire continuum of substance use. This is the hallmark of universal health coverage (UHC) and ensuring well-being for all. It is estimated that primary health care (PHC) interventions across low- and middle-income countries could save 60 million lives and increase average life expectancy by 3.7 years by 2030. Access to primary health care is a recognised human right and a strategic approach to achieving UHC.

2. What are the standards of SUD care in primary health care?

Primary Health Care (PHC) is defined as essential health care that’s accessible to individuals and families in the community, in ways that are acceptable to them, through their full participation, and at a cost that the community and the country can afford. PHC can meet up to 90% of a person’s healthcare needs throughout their lifetime, including mental health conditions and substance use. This integration is a recommended key strategy that countries must include in their mental health care model.

SUD care in primary health care serves as a primary and secondary prevention strategy. Primary to discourage use before it has been contemplated through psychoeducation and secondary aimed at changing behaviours (in this case potentially addictive behaviours) or harm reduction. It can also serve to improve patient outcomes through early intervention.

Several models have been designed to bring care for persons living with substance use disorders into primary health settings informing integrated and accessible care:

Colocation model: In this model, a centralised approach is employed, offering substance abuse treatment, primary medical care, and mental health services all at a single site. This model is widely used in countries like Australia and the Netherlands —essentially a “one-stop-shop” method. This model seems to work better in strong primary health systems, the availability of multi-professionals evenly spread across locations, and better health insurance systems. This model improves access, promotes collaboration and reduces stigma.

Distributive model: In this model, all sites offering care (primary care, behavioural care, etc) are linked through effective systems, enabling patients to move between services as needed. This model is applied in countries like India, China, Ethiopia, and Uganda.

Primary Care Behavioural Health (PCBH) model: This model resembles the colocation model but differs in that, a behavioural health professional (working as a “consultant”) shares clinical space with primary health providers and lends efforts to enhance the primary care team’s ability to manage behavioural health problems including SUDs, while improving primary care services for all clinic population. This “consultant” sees all patients at the clinic as soon as possible after referral and is part of patient follow-up. This model has been successfully used in the United States.

This PCBH model gives birth to the behavioural-health-linked model where non-specialised primary health professionals are trained and supervised to offer some first-line behavioural health services with support from specialised behavioural health professionals.

Regardless of the model used, strong linkages between primary health care, mental health, and SUD services yield significant benefits:

- For patients: Better overall care, improved satisfaction, and early detection.

- For clinicians: Inclusion of substance use history in diagnosis and improved adherence to treatment plans.

- For mental health and SUD professionals: Enhanced treatment outcomes, relapse prevention, and continuous quality improvement.

- For society: Reduced health care costs and improved population health outcomes.

SUD in Primary Health Care: what has worked?

Several successful integrated interventions demonstrate the effectiveness of incorporating substance use disorder (SUD) care into primary health care systems. Some of these are:

The CATALYST project in the United States: The CATALYST project was initiated in 2016 at Boston in Massachusetts, United States. This program helped young people who use substances lead healthy lives through holistic, team-based care. CATALYST accepts referrals for patients aged under 25 who use substances. They got primary care, treatment for major psychological disorders, and other substance-related care for opioids, alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and stimulant use disorders. There was also access to family therapy. They leveraged the colocation model, providing access to physicians, nurses, psychiatrists, social workers, a paediatrician with an addiction subspecialty and a programme manager. This programme saw greater outcomes, especially in the engagement of treated patients. It recorded a massive 28.5% re-engagement, compared to 9% and 17% reported in similar office-based treatment studies (.

SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment) project in Lagos, Nigeria: This project, which is novel in Nigeria, began in 2025 in a bid to implement the recommendations of the National Drug Control Master Plan of the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crimes and the Federation of Nigeria (2019-2025). This document states the integration of substance use care into primary healthcare services as a major outcome to reduce drug demand. The SBIRT project is a novel idea in Nigeria to put that policy into practice by training primary health physicians on screening, brief interventions, and referral to treatment competencies. The programme also included the design of a curriculum to guide practice for these physicians. The initial training was conducted in January 2025 with 33 physicians across all local government areas of Lagos State in collaboration with government agencies, CSOs, and professionals.

Community-Based Treatment and Care for Drug Use and Dependence in Southeast Asia: Robust community-based interventions that Screening, counselling, primary health and referral services are provided in health centres. Patients from the community centres are referred to primary care and substance use specialty services based on needs.

World Organization of Family Doctors- WONCA’s Leadership and Advocacy Program: The World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) Leadership and Advocacy Program for Integrating Mental Health and Primary Care addresses the global challenge of integrating mental health into primary care, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, by empowering young family doctors with leadership and advocacy skills. The purpose is to enable these physicians to be agents of change in their practicing communities. It trains, mentors, and supports them to lead practice transformation efforts and be empowered with policy-influencing skills to integrate mental health and primary care in their local settings, within their health system constraints and assets. The scholars engage in a curriculum covering leadership, advocacy, stigma and discrimination, integration of care, team-based models, practice transformation, burnout, and resilience. To date, there has been a successful alpha and beta pilot producing 20 scholars, and rigorous evaluation to ensure measurable progress.

Alcohol Use Counselling in India: Investigate the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of: identifying and recruiting men with probable AD (alcohol dependence) in primary care; delivering a brief treatment for AD by lay counsellors in primary care counselling for alcohol problems (CAP) intervention was used to treat alcohol dependence in primary care. This intervention was delivered across 18 primary health centres in Goa, India to adult men who had a diagnosed alcohol use disorder (AUD). The interventions saw a reduction in harmful drinking behaviours through CAP delivery in primary care services.

Culturally adapted SUD therapy for HIV patients in Kenya: This project involved the development and delivery of culturally adapted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients. Eligible recipients were persons ages 18 and older enrolled as HIV outpatients (receiving or eligible to receive antiretroviral) who satisfy the hazardous or binge drinking criteria. The aim was to achieve abstinence from alcohol and/or encourage approximations to abstinence amongst served patients.

Brief Intervention for poly-substance users in Brazil: This intervention administered brief interventions to patients in 30 primary health care (PHC) units, two health centres, and one outpatient setting. This intervention used the World Health Organization’s ASSIST and its linked Brief Intervention (BI) for illicit drugs (cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) and opioids). The program also evaluated the effectiveness of BI for one substance for other risky drug use. Eligible participants were those who screened with a moderate risk of SUD.

The FAST PATH program in the United States: There is a relationship between SUD and the HIV status or high-risk status of individuals. Hence, integration of both care is effective for improving health outcomes. Also, considering the depression-prone risk of people living with HIV (PLWH), the need to integrate mental health care as part of primary care for this clinical population is further emphasised. This program aimed to coordinate care for HIV or at-high-risk HIV patients who are also in need of addiction and/or primary health care. It features a cohort study of a comprehensive addiction treatment for 265 patients with HIV or at high risk of HIV infection. Patients received primary care and addiction pharmacotherapy as well as individual and group counselling. At the end of the 6-month study, 64% of the patients met the criteria for engagement, while the number of substance-dependent patients decreased from 100% to 49%. The FAST PATH program successfully engaged and treated patients in a primary care-based addiction treatment program. However, the program revealed that self-reported depression at baseline was the only predisposing characteristic of studied patients associated with substance dependence after 6 months, further buttressing the need for an integrated SUD and mental health care for this population.

3. What challenges exist

Whilst more interventions on the integration of SUD care into primary health care exist, it is important to be clear on the persistent challenges towards effective integration of SUD care in primary health, including:

For people living with SUD:

Financial barriers: Limited finances and out-of-pocket burden of seeking SUD care in addition to PHC (especially for LMIC).

Stigma and self-criticism: Social stigma and internalised shame deter individuals from seeking care.

Cultural and commercial influences: Norms surrounding alcohol and tobacco use, reinforced by aggressive marketing, hinder regulation, as well as prevention and treatment efforts.

For providers:

High workload: Heavy patient caseloads limit time for additional responsibilities.

Competence gaps: Limited training and confidence in conducting SUD screening, brief interventions, and referrals.

Time constraints: Lack of time during consultations to address substance use adequately.

Lack of confidence in administering SUD screening, brief intervention and referral.

Limited referral systems: Limited access to specialists, weak interprofessional collaboration, and non-existent or inefficient referral pathways.

For programmes and systems:

Coverage limitations: Inefficient or absent health insurance systems that exclude SUD and mental health services in some contexts.

Limited referral networks: Limited local resources and poor linkages for specialised SUD treatment..

Funding gaps: Inadequate financial support for integration projects.

Deficit in technical assistance: Lack of structured support for workforce training and implementation.

4. Where next? Recommendations

To improve the prevention and primary care and outcomes for people living with SUD, the following actions are recommended:

For health professionals: Professionals (especially those in primary care in community centres, NGOs, special population health care, HIV care, Maternity, etc) should ensure to get basic education on SUD screening and referral models. Collaboration between professionals should be encouraged to promote effective access and optimization of local resources for SUD care.

For policy makers: It is recommended that policies for affordable health care services, health insurance that covers SUD and mental health care should be enforced as accessible to all. It is also recommended that collaboration between professionals be enforced through policies that allows for cross-consultation and cross-ownership of outcomes by governmental agencies, CSOs and other stakeholders.

For advocates: Advocates can extend their lenses to the gaps in primary health care especially on the SUD care. Advocacy can also close the gap of information about available care options making it easier for more people to access it.

For funders: In many nations, mostly LMICs, mental health and substance use budgets are lean despite the glaring problems. Funders can allocate more resources towards mental health care and SUD care in primary health care. They can also ensure that funded projects in SUD care are sustainably designed for adoption into primary health care or community-based interventions in a bid to promote availability of options.

For researchers and academics: More research still needs to be done to evaluate:

Effectiveness of various integration models.

Best practices on referral and post-referral follow-up.

Long-term impact of integration.

Identify stigma and systemic barriers to patient seeking care for SUD in primary health care settings.

Impact of integration on chronic diseases and co-occurring mental health disorder, etc.

If you are interested in the umbrella review and the evidence underpinning this Need2Know brief, download the PDF version, which includes a link to all papers.